Source: Shaoshu Pai Investment

Now, if you ask many investors, especially growth investors, how the market should respond, the answer you often get is: I don't know.

Indeed, there seem to be many uncertainties in the macroeconomic environment: economic growth appears less optimistic, the Federal Reserve’s policy remains unclear, geopolitical tensions could escalate again, and whether Trump will continue to influence global dynamics, followed by TACO.

Similarly, the grand era of artificial intelligence that growth investors have heavily relied on in recent years seems to have reached a plateau. Following significant gains in AI-related investments and stocks, concerns have grown about whether this momentum can be sustained and whether killer applications will truly emerge.

Similarly, the grand era of artificial intelligence that growth investors have heavily relied on in recent years seems to have reached a plateau. Following significant gains in AI-related investments and stocks, concerns have grown about whether this momentum can be sustained and whether killer applications will truly emerge.

At this juncture, reflecting on the thoughts of those who came before us may help us cut through the noise and identify the key issues.

The year 2021 marked James Anderson's final year at the helm of Baillie Gifford's flagship product, the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust (SMT). In May of that year, he penned his last annual letter to shareholders. Coincidentally, the circumstances at that time bear many similarities to the present day.

The U.S. stock market experienced substantial gains from 2020 to 2021, and its future trajectory has become a topic of widespread interest.

Following the tremendous surge driven by internet and new energy applications after 2021, questions remain about whether this growth can continue.

In 2021, supply chains were disrupted due to the pandemic, leading to a sharp rise in inflation, rapid interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, and significant shifts in the economic landscape.

……

In the current environment, James Anderson has also encountered 'rhymes of history' in his time. How he views his own choices and how he approaches investment management are all worthy subjects for us to learn from.

--------Anderson's Letter to Investors----------

After many years of unremarkable commentary, perhaps I may be permitted a bit more candor in my twenty-second, and final, letter to SMT investors. Over the past two decades, I have misunderstood and misjudged many things, but I have become increasingly convinced that my greatest failure has been a lack of radicalism. To be frank: the world of traditional investment management has irreversibly collapsed. Its demands far exceed the classic 'six impossible things before breakfast' proposed in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Some Arguments

But let me first attempt to articulate my beliefs. Hopefully, they will not require future questioning, nor will my successors doubt these arguments over the coming decades. As the world changes, we should all adapt accordingly. Indeed, this is an appropriate starting point.

The past investments belonged to the narrative world of Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, whom Warren Buffett greatly admired. To illustrate the changing world, Graham defined growth stocks as those capable of doubling earnings within a decade. This idea was widely embraced by the media, much like how Alice’s rabbit hole depicted the environment of the late 19th century.

However, a profound transformation occurred in the investment community in the mid-1980s. Let us examine some recent data:

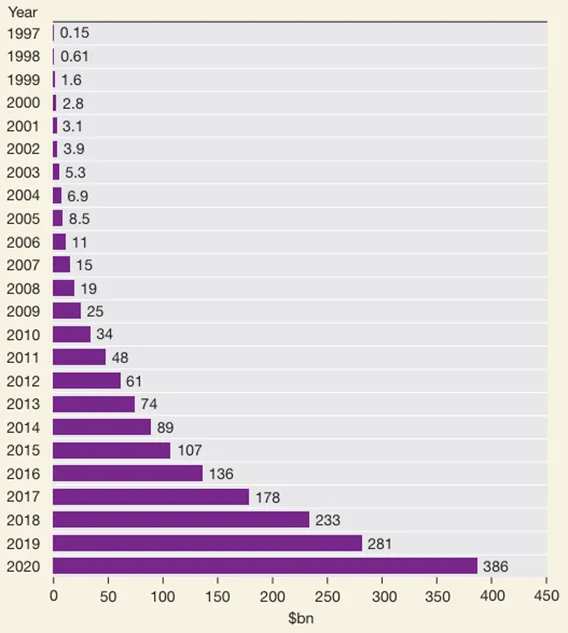

Many of you will likely recognize these figures as Amazon’s annual revenue. At the time, they significantly underestimated the company's progress because fiduciary responsibilities made them conservative. However, over the past two decades, the company’s stock price has grown at a compound annual rate of 41%. For those who prefer profit metrics, such as Graham, Amazon generated $31 billion in free cash flow in 2020. Since the advent of digital technology, this pattern of sustained hypergrowth with increasing returns to scale has become increasingly evident, with Microsoft being the first example (still growing 35 years after becoming a public company).

Investing unfolds amidst these outliers. Regardless of what the CFA curriculum instills in the young and inexperienced, in the real world, one cannot construct a portfolio by selecting risk and return levels along the classic bell-shaped probability curve (normal distribution). The bell curve neither accounts for the profound uncertainty of the world nor acknowledges the extreme skewness of return distributions.

The essence of investing lies in seeking companies with characteristics that could achieve extreme and successful compounded growth. However, the eternal temptation to divert attention by searching for minor opportunities in mediocre companies over short periods must be resisted. This requires conviction.

For such companies, stock prices can experience significant declines. A 40% drop is not uncommon. Stock charts that appear as relentless upward-sloping lines from the bottom left to the top right are never as smooth and straightforward as they subsequently seem.

So, how do we identify these stocks with extraordinary potential? How do we gain the conviction to allow compounding to work its magic? As Jeff Bezos steps down as CEO, let us reflect on what we discovered, how we endured, and what we missed.

In the narrative of great investments, the most recurring common factor is that the company possesses open-ended growth opportunities. It should strive tirelessly, never confining itself within predetermined boundaries or timelines. It is led by visionary leaders or management who think like founders and embrace a unique business philosophy. It almost always engages in independent thinking derived from first principles.

Arguably, all these characteristics could have been identified in Amazon from the very beginning. If you read Amazon’s first shareholder letter in 1997, it becomes evident that this was an exceptionally ambitious and patient idea. Frankly, our failure to recognize this stemmed from our own limitations, rather than a lack of clues. We were simply too focused on understanding market trends, overly preoccupied with short-term performance, and constructing poorly balanced portfolios driven by fear of downside risk. This prevented us from becoming steadfast company owners.

By 2005-2006, as investors, we had improved enough to recognize some potential and withstand greater challenges. This also helped us endure many difficult periods: Amazon's stock price fell 46% from its peak in 2006. I grew accustomed to client meetings where peers in the investment community declared Amazon their favorite short-selling target. They particularly disliked the costs associated with Prime and Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud, the latter of which became AWS. Gradually, we learned and understood its strategy. However, we made a mistake when our Amazon holdings approached 10% of total assets—we reduced our Amazon position. For this, we should apologize; it was wrong.

It was only in recent months that our enthusiasm for Amazon began to wane. The market now recognizes Amazon’s value, and the company is secure and acceptable in terms of asset safety. It no longer has a founder as CEO. We worry that, to use Bezos' unparalleled phrasing, Amazon may no longer be in 'Day One,' even though the road ahead remains long and investing in Amazon can still be profitable.

Time Horizon, Possibility, and Fundamental Uncertainty

The list of reasons why obsessing over long-term decision-making is too lengthy to enumerate here fully. However, one branch of long-term investing seems exceptionally important yet is often overlooked by investors. An inherent feature of the efficient market concept is that all available information is already reflected in stock prices. Only new information matters. This rationale is used to justify the near-insatiable attraction to news such as listed companies’ earnings announcements and macroeconomic headlines. In turn, the power of short-term financial incentives reinforces this.

Thus far, this has been a critique of the standards of short-term investing. We agree with this view, but there is more to consider. If you believe all information is reflected in stock prices while also deeming short-term investment outcomes important, this creates an intellectual vacuum.

If that is the case, we, as investors, have no need to interpret the future.

This may sound abstract, but it is not. Let us use Tesla to illustrate the puzzle. Seven years ago (in 2014), when we first invested in Tesla, we believed, or more accurately, observed that the rules and pace of learning about battery performance and manufacturing electric vehicles were already well understood in practice and well articulated in academic research. Since then, both the rate of data improvement and confidence levels have continued to rise. This made our investment in Tesla almost inevitable because at some point, electric vehicles would become better, cheaper, and more environmentally friendly than internal combustion engines. When a challenger with an improvement rate of over 15% meets incumbents who previously improved at 2-3%, what is happening to Tesla now is precisely the result.

Since Tesla is the only significant Western electric vehicle company, our investment decision was not difficult. We simply needed to heed expert advice and wait. But most investors do not listen to experts. Instead, they follow brokers and media opinions, being swayed by fearmongering and numerous short-sellers. Headlines tell them that Tesla will face tough times next quarter and that Elon Musk speaks too bluntly. For us, this represents a clear market inefficiency, offering patient investors the potential for extremely high returns. Too many investment decisions are marginal judgments. The likelihood of electric vehicles prevailing is very high. We do not need insight or clever models to see it – just patience and trust in experts and companies.

The uncertainty lies elsewhere. It is tied to other geographical locations – given the level of competition in China, there is significant uncertainty about whether Nio, one of our investments, can thrive or even survive (Editor’s note: SMT has exited its position in Nio). This also applies to Tesla’s own return calculations, especially now with its ambitions for autonomous driving, which could transform the economics of the company. However, despite our efforts, it seems improbable to estimate the likelihood of success for an entirely new endeavor or to predict the exact cash flow outcomes after success. To us, it is peculiar that brokers, hedge fund experts, and market commentators claim they can decipher the future and set a precise numerical target for Tesla's valuation.

Perhaps they are all geniuses. But we are not. We should respect and endure uncertainty, striving to identify areas where extreme upside potential may emerge and patiently observe.

This is not a debate between growth and value.

Tesla is a key example of investing in the core issues of our era. It is not about the relationship between growth and value, nor the level of market enthusiasm, nor the economic growth rate or pandemic progress in 2021. It is about understanding change.

How it happens, how much change occurs, and its impact.

Refusing to accept this may reflect a desire for a sense of security in investing that is ultimately illusory, but it also symbolizes a broader crisis brought on by economic thinking overly focused on equilibrium mathematics. If we shift our attention to studying profound changes, we will be less tempted to believe in eternal truths of investing that will forever remain in our textbooks.

This does not mean “this time it’s different,” but rather signifies a refusal to acknowledge that the world and investing remain perpetually the same. The only rhyme is that, in the long run, the value of stocks reflects their ability to generate long-term free cash flows, yet we only have the simplest, vaguest clues about these outcomes. But in this era of profound transformation, those who define value by short-term price-to-earnings ratios are in for trouble ahead.

The future

In the next decade, it is almost certain that we will witness changes more painful, inspiring, and dramatic than anything we have seen before. I deeply envy the opportunities and experiences my successor will enjoy. Even in the past year, amidst the tragedy of the pandemic, there were signs of what is to come. I am not referring to the proliferation of digital platforms helping to mitigate the constraints of the pandemic, but rather the rise of forces that are more dramatic and significant. From the extraordinary revolution that will improve our society (the mainstreaming of renewable energy), to emerging miracles in synthetic biology, to the possibility of medical innovation becoming a series of routine beneficial revolutions rather than a complex and frustrating drain on resources, the potential is immense, and the threat to old empires is imminent. Without participating in venture capital, it would be difficult to gain an education in these exciting fields. We will always be grateful for finding ways to interact with extraordinary minds and energies in this unknown world.

Frankly speaking, five years ago, I would have been astonished by the opportunities and chances we encountered as usual. We were fortunate. It was a privilege. Our former board member, John Kay, taught us many things, but perhaps the most valuable lesson was the role of indirect thinking. By engaging with visionary individuals and companies, we sought insights into the future world.

We often feel overwhelmed and confused during the process, rather than gaining understanding. But this is our plan.

Investment outcomes are nothing more than the ultimate result of each of our mindsets and processes.

We need to remain unconventional. Not only that, we need to become more radical and prepare to be even more so. We have always claimed to learn from the outstanding leaders we have had the privilege to encounter in managing Scottish Mortgage (SMT, Baillie Gifford’s flagship product). If possible, I would like to conclude my speech by quoting two of them. The first is Noubar Afeyan, founder of Flagship health investors and chairman of Moderna. A year ago, I would have needed to elaborate on Moderna's purpose at this point, but now it is a delightfully redundant task. However, the comment I wish to quote transcends Moderna and vaccines:

“Let me say, perhaps somewhat obviously… we must be willing to entertain unreasonable propositions and unreasonable people in order to make extraordinary discoveries, because the notion that perfectly reasonable people doing perfectly reasonable things leads to massive breakthrough ideas does not hold true for me.”

No industry is more skeptical of such unconventional practices than investment management. We need to rethink investment management from first principles. We need to help create great companies that embrace the extraordinary. Clearly, no one exemplifies and articulates this better than Amazon’s Jeff Bezos. His recent, and last, letter concluded with an entreaty:

“We all know that uniqueness, originality, is valuable. What I’m truly asking you to do is to embrace that uniqueness and realistically assess how much effort it takes to maintain it. This world wants you to conform and will do everything it can to attract you into mediocrity. Don’t let that happen. You will have to pay a price for being different, but it is worth it.”

AI Portfolio Strategist!One-click insight into holdings,Fully grasp opportunities and risks.

Editor/jayden