Source: Smart Investors

Today’s reading is another lengthy piece, which I’ve gone over three times.

An opus penned in 2019 by James Anderson, often referred to as the 'world-class collector of great companies' — titled 'Graham or Growth?'

Anderson begins by writing: 'We need to more clearly articulate the underlying logic of 'high-growth investing,' while also challenging those harmful stereotypes about how the stock market operates. This article represents my attempt to do just that.'

Anderson begins by writing: 'We need to more clearly articulate the underlying logic of 'high-growth investing,' while also challenging those harmful stereotypes about how the stock market operates. This article represents my attempt to do just that.'

James Anderson graduated from the University of Oxford with a degree in history, later pursuing further studies in Italy and Canada, earning a master’s degree in international affairs in 1982. He joined Baillie Gifford in 1983 and became a partner in 1987. Starting in 2000, he served as the fund manager for the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust (SMIT), marking the beginning of his legendary 20-year investment career.

In the minds of most Chinese investors, Anderson is considered a proponent of 'extreme growth,' seemingly at odds with Benjamin Graham's value-oriented tradition.

However, after reading this lengthy article, you will find an interesting fact: Anderson has probably read 'The Intelligent Investor' more thoroughly and thoughtfully than most who call themselves 'disciples of Graham,' and he has been more candid in practicing and testing those classic principles in today’s world.

If one were to identify a main thread in his thinking, it could be understood from two perspectives: the divergence between high growth and value, and their true commonalities.

The first point is his acknowledgment of an existing and growing divergence.

In Graham’s world, most companies would eventually return to a steady state after experiencing fluctuations: growth stocks are hard to sustain over the long term, as excess returns are eroded by competition, diminishing returns to scale, and the unpredictability of life. Therefore, low price-to-earnings ratios, low price-to-book ratios, and sufficient margin of safety serve as the most reliable starting points.

Anderson, however, is faced with a different scenario:$Microsoft(MSFT.US)$、 $Google-C (GOOG.US)$ 、$Amazon(AMZN.US)$、 $Meta Platforms(META.US)$ 、$Tesla (TSLA.US)$, including those we are familiar with $Alibaba(BABA.US)$ 、 $Tencent (00700.HK)$ . These companies maintain high growth even at extremely large scales, and their return structures resemble a 'power-law distribution,' where a small number of winners determine the majority of returns. Underlying this trend is the rise of technology, data, network effects, and 'increasing returns to scale,' as well as the shift from an asset-intensive economy to a knowledge-intensive one.

He is not saying that Graham was wrong but rather pointing out: if the underlying economic structure has changed, simply relying on the experience of 'mean reversion' and 'low valuation' may no longer be sufficient.

But the second point is equally important: in truly core areas, the divergence between high growth and value itself is not so significant.

Andreessen is well aware that what Graham truly cared about was never low P/E ratios themselves, but whether one is honestly estimating a company’s long-term cash flow, whether one has the awareness to prevent major losses, and whether one treats stocks as part of a business rather than mere chips… These principles are precisely what he believes he must adhere to.

He repeatedly emphasizes the need for a longer time horizon, more serious corporate research, and a clearer sense of investment purpose; he appreciates the value tradition's emphasis on patience, sensitivity to corporate governance and capital discipline, but opposes reducing them to a few mechanical financial indicators.

Moreover, in the article, he repeatedly cites Munger’s 1996 remarks on$Coca-Cola(KO.US)$The classic conception and articulation, 'If I could also tell a story about Coca-Cola's growth in 1884 like Munger, I would feel very gratified. Isn't that a more advanced logic of long-term growth?'

Recalling Han Shenghai, one of the authors of 'The Baillie Gifford Way,' when he spoke about why Baillie Gifford can practice long-termism, he believed it relates to worldview and business models. What is a worldview? It’s the belief that technology will reshape the world and change human lives; but at the same time, the high uncertainty of real-world development poses enormous challenges to investment.

When watching many of James Anderson’s speeches and interviews, this worldview is ever-present, and this is also where the underlying logic of his 'growth investing' differs significantly from many other similarly labeled investment approaches in the market.

Finally, I strongly recommend once again that everyone patiently read the entire article.

01, Two Traditions, Yet Only One Body of Literature

Fifteen years ago, when we first attempted to explore and explain our passion for 'growth investing,' it was natural to want to draw lessons from our predecessors. However, the problem was that there was almost no literature to reference. Among all the classics of investment, the only work that truly advocated 'growth investing' was Philip Fisher's 1958 publication, 'Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits.'

Fifteen years have passed, and overall, the market and reality have been kind to growth investors. But regrettably, even today, whether on paper, online, or in podcasts, it remains difficult to find materials that systematically defend 'resolute, long-term growth investing.' The investment community seems to generally lack an attitude that investment views should be adjusted when facts change.

Meanwhile, the self-evident belief that 'value will ultimately prevail' remains deeply entrenched. Advocates of value investing often exude a sense of moral superiority, as if growth investors were merely speculators chasing gains and fleeing losses, lacking conviction.

As a result, even though growth strategies have consistently outperformed passive indices in the market over the long term, many institutional clients still insist on rebalancing their allocations back to the value investing camp.

In stark contrast to the sparse literature on growth investing, value investing boasts a comprehensive intellectual tradition and classic works, ranging from Buffett and Munger to (Seth) Klarman and (Howard) Marks, with a long and rich heritage. Value investing even has its own 'Bible,' or at least an 'Old Testament'—*The Intelligent Investor*.

I revisited Benjamin Graham’s classic work and referenced Jason Zweig’s excellent annotations. Undoubtedly, this is a great book that has inspired generations of outstanding investors.

However, I do not believe it negates the possibility of growth investing.

On the contrary, against the backdrop of profound changes in today’s economic structure and corporate forms, it instead offers us another interpretation path worthy of serious consideration.

Graham defined so-called 'genuine growth stocks' as companies that could double their earnings per share within a decade. However, he also pointed out that such companies often carry a distinct speculative flavor due to being overly hyped. Therefore, he preferred to invest in larger companies that received less market attention.

He reminded us that growth stocks are often more vulnerable to significant declines during market downturns; even IBM, at the height of its success, experienced two instances of its stock price being halved.

His ultimate conclusion was: 'Companies capable of achieving long-term, rapid, and sustained growth are extremely rare; similarly, large companies that fail completely are also few. The development trajectories of most companies are characterized by fluctuations.'

These few sentences can almost be regarded as a distilled expression of his belief in 'mean reversion,' a core concept later revered as a fundamental tenet of investing.

Even so, he reiterated his most famous maxim: 'Margin of Safety,' even going so far as to use all capital letters to emphasize its fundamental importance.

What are the core principles of Graham’s investment philosophy?

He clearly stated at the beginning of the book: "One of our main recommendations is that investors should focus on companies whose stock prices are not significantly higher than their tangible asset values… Adopting this prudent and conservative strategy often proves more reliable in the long run than investing in exciting but highly risky growth stocks."

Graham did not merely theorize. He always supported his arguments with specific case studies and long-term data, presenting his reasoning in a methodical manner. Citing the performance during market crashes, he pointed out that growth-oriented mutual funds failed to deliver excess returns.

More importantly, his own consistently outstanding investment track record served as an implicit and persuasive endorsement, though he never boasted about it.

However, if we extend the timeline to the past decade, it is evident that reality has deviated from the world Graham observed.

During this period, those 'less popular large companies' did not yield ideal investment returns; instead, the true excess returns came from the 'popular and even high-risk' growth stocks that Graham might have avoided.

If we extend the timeline further and examine individual stocks, this trend becomes even more pronounced.

Microsoft is a typical example.

In 2008, its annual revenue was USD 60 billion, with earnings per share of USD 1.87, led by Steve Ballmer. At that time, it was embroiled in controversies over 'growth stagnation,' faced heavy regulatory pressures, and its attempted transformation through acquisitionsNokia (NOK.US)ended in failure.

However, a decade later in 2018, Microsoft achieved revenue of $110 billion and earnings per share of $3.88, while maintaining double-digit growth, serving as a model for stable expansion amid adversity.

More importantly, since its initial public offering in 1986, Microsoft's net profit has grown from $24 million to $30.27 billion in the fiscal year 2018, with an annual compound growth rate of 24%, while its gross margin remained above 30%.

This may be one of the most remarkable long-term growth records in modern corporate history. Few could have foreseen its continued success, and even fewer would have taken seriously those investors willing to firmly bet on it at the time.

It is precisely this extraordinary success that warrants our deep understanding and reflection.

The same is true for Google. In 2008, Google generated revenue of $21.8 billion and net profit of $4.2 billion; by 2018, its parent company Alphabet reported revenue of $136.8 billion and net profit increased to $30.7 billion.

Its business logic is not actually complicated. As Buffett frankly admitted in 2017: “We should have been smart enough to understand Google, but we failed in our duty.”

$Netflix (NFLX.US)$(Netflix) and Amazon are similarly notable cases.

Graham might have scoffed at their business models, which tolerated long-term losses. But if we focus on the growth of their user base and revenue, how should we interpret the relationship between this potential and its realization?

As for$Alibaba(BABA.US)$Companies like Tencent have never truly met the standard of a 'margin of safety,' yet there is no denying that they have driven the evolution of technology, commerce, and social structures.

I want to emphasize that by listing these cases, I am not reviewing the report card of the past decade but rather illustrating that many realities have diverged from Graham's judgments within the time frame he adopted.

These realities are not counterexamples but starting points for understanding the profound changes that have occurred today.

Graham himself, along with his many outstanding followers, were great thinkers and investors. However, if their core ideas are now facing challenges from reality, we have reason to believe that some fundamental rules of the world may indeed be changing.

This change is a crucial element in understanding the future direction of investment—far more important than reviewing past performance.

02. Future returns are highly uncertain

Before proceeding further into the discussion, we must first examine the limitations of our understanding. This is extremely important.

Whether it is Graham’s firm belief in 'though short-term fluctuations occur, things will eventually be correct in the long run' or the often baseless assertions made by many market commentators and analysts today, I believe it is necessary to maintain a deeper level of skepticism about the so-called 'certainty of investment outcomes.'

This is also the direction that more rigorous scientific and mathematical research is gradually guiding us toward.

Imagine attempting to deduce 'universal laws of market operations' based solely on the limited experiences of a few countries over the past 150 years. In the eyes of many distinguished scholars, such an endeavor appears almost absurd.

Nobel laureate and co-founder of the Santa Fe Institute, Murray Gell-Mann, repeatedly emphasized that we are often too quick to regard what has already happened as inevitable, as if it were the only possible outcome. The range of possibilities in reality, in fact, is far richer than we are willing to acknowledge.

He once wrote: We and the world we inhabit are more akin to 'frozen moments of historical contingency.'

An example he cited more than two decades ago still resonates profoundly today—

Henry VIII was able to inherit the throne of England only because his older brother, Arthur, died young; Arthur, notably, was a man of entirely different character. He also married Catherine, a union that later had a profound impact on England's Reformation.

Gell-Mann sarcastically remarked that this chain of historical contingencies ultimately led to 'the marital farce of Prince Charles and Diana.' If he were speaking today, he might have added: All of this eventually gave rise to Brexit.

Another example may carry even greater cautionary significance.

In the 'Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show,' Annie Oakley gained fame for her skill in shooting cigarettes off with a gun. She would often invite audience members onstage to participate in her act. Most of the time, no one volunteered, leaving her husband to pretend to be an audience member to fill the role.

However, during one European tour, a brave volunteer stepped forward. Unfortunately, Annie had been heavily intoxicated at a beer garden the previous night, and facing this unexpected challenge, she became extremely nervous. Nevertheless, with a high degree of professionalism, she ultimately succeeded in completing the performance.

This story may seem unremarkable, but it hides a stunning detail: That volunteer was none other than the young Kaiser Wilhelm II, a figure who would later profoundly influence the fate of the world.

The causes of World War I remain a subject of debate, but few would deny that Wilhelm's aggressiveness and personality flaws had a significant impact on the outbreak of the war. If Anne's hand had trembled at that moment, or if she had been drinking Belgian beer with a higher alcohol content instead of German beer, world history might have been vastly different.

These incidental historical episodes may themselves seem trivial, but they reveal fundamental issues within financial and economic theories.

It was on October 19, 1987, that I completely abandoned the two tenets of 'predictability' and 'market efficiency.'

That day,$S&P 500 Index (.SPX.US)$the market plummeted by 20% without any major news. Such a dramatic shift makes it difficult to explain using traditional theories. Of course, everyone comes to terms with reality through different paths, but it is certain that today's markets (think 2008) have long departed from the rational image depicted by classical equilibrium economics.

The world we live in is a complex system—unpredictable, irreducible, and not always explicable.

As Melanie Mitchell noted in her book Complexity: The operation of capital markets resembles the human immune system in its strangeness, difficulty to comprehend, and capacity to perplex.

As Murray Gell-Mann put it, those particles—each of us—equipped with brains and emotions, form a world that is challenging to model.

The outcomes in reality are merely one among infinite possibilities.

The issue is that the incidental outcomes of this 'one-time freeze' often reshape our future trajectory in unimaginable ways.

As football commentators often say, 'One goal can change the entire match.' The same applies to the business world. We cannot turn back time or control chance.

Microsoft’s success can be explained by various underlying logics, but it is also deeply rooted in chance. For instance, IBM initially did not approach Bill Gates to develop the operating system but was advised to contact a company called Digital Research. However, its founder, Gary Kildall, was engrossed in hot air ballooning at the time and missed the meeting, prompting IBM to turn to Gates instead.

Compared to Henry VIII’s marriages or Microsoft’s early business decisions, the market environment we face today is far more complex, path-dependent, and unpredictable.

Simply acknowledging that 'future returns are highly uncertain' may already be significant enough.

The Graham-style value investing creed, as well as the extreme performance of platform companies like Microsoft and Google, may merely be 'near-random outcomes' resulting from the interplay of various variables during specific periods.

We should not mistake them for eternal truths of the financial world.

Section 03: How to View the Future Landscape

However, even so, if we wish to speculate on potential investment paths in the future, we must understand the underlying structural changes in the global economy.

This understanding goes far beyond short-term speculation such as 'predicting next year's GDP or interest rates,' requiring us to consider possible structural shifts over the next ten to twenty years, along with their direction and magnitude.

Currently, the market often views style rotations between 'growth vs. value' or 'extreme growth vs. reasonable growth (GARP)' as purely financial variables, overlooking the underlying economic substance.

However, in the long term, what truly dominates market returns are not these labels, but the ongoing contest between 'systemic change' and 'relative stability.'

In a world trending toward stability and incremental progress, the Berkshire Hathaway model holds greater advantages; in an era where repetition outweighs transformation, Graham’s philosophy of 'volatility and mean reversion' serves as a powerful tool.

But if the world is undergoing radical transformation, the conclusion will be fundamentally different.

Schumpeter once wrote: 'At the core of nearly all economic phenomena, difficulties, and problems in capitalist societies lies innovation.' This statement, almost regarded as common sense, remains valid to this day.

What appears to be a recurring financial crisis is, in fact, a structural upheaval driven by information technology. Meanwhile, other industries have stabilized under the influence of globalization.

This has also fueled a longstanding divergence regarding whether innovation is stagnating: on one side stands Gordon-style pessimism, while on the other is Silicon Valley's techno-optimism.

Our assessment is that future transformations will be even more intense, bringing about disruptions of greater magnitude. The forces that once dismantled the newspaper industry and DVD rental businesses will sweep through more sectors on an even larger scale.

In fact, 2018 had already released numerous warning signals. Even traditional investment banks began to reflect: can the terminal value of oil companies still hold up as fossil fuels decline?

We are entering an era where 'mean reversion' becomes increasingly powerless and 'creative destruction' takes center stage. By 2030, the economic order established post-war may appear antiquated.

Schumpeter's words serve as a fitting conclusion: 'This civilization is rapidly declining. We can cheer for it or lament it; but we cannot pretend it is not happening.'

04, A World Thoroughly Transformed?

What if the world has become so unfamiliar that we are unable to analyze it in any effective way?

This transformation may be as profound and irreversible as when agrarian societies first faced the Industrial Revolution. Not only have the rules of the game changed completely, but even the definition of economic activity has become blurred.

Against the backdrop of such fundamental uncertainty, continuing to believe that any old patterns of behavior will persist over the long term, and basing return expectations on this belief, is dangerous. Especially when we attempt to predict the future using quantitative tools like 'historical volatility,' it becomes a breeding ground for misjudgment of risks.

What we can truly do is continuously explore various possibilities. Maintaining an open, humble, yet prepared mindset may be the most rational way to respond.

Another viable approach is to embrace the framework proposed by Nassim Taleb: constructing a portfolio that is 'exposed to black swan events,' while also acknowledging that such events are unpredictable and extremely rare.

Though this approach runs counter to traditional financial principles, it is closer to the essence of our times.

When modern portfolio theory still dominates both academia and practice, and its underlying equilibrium assumptions are repeatedly contradicted by reality, we indeed have reason to worry.

In our research and collaborative projects, we strive to re-examine the importance of history in economic research through a global, long-term, interdisciplinary historical perspective.

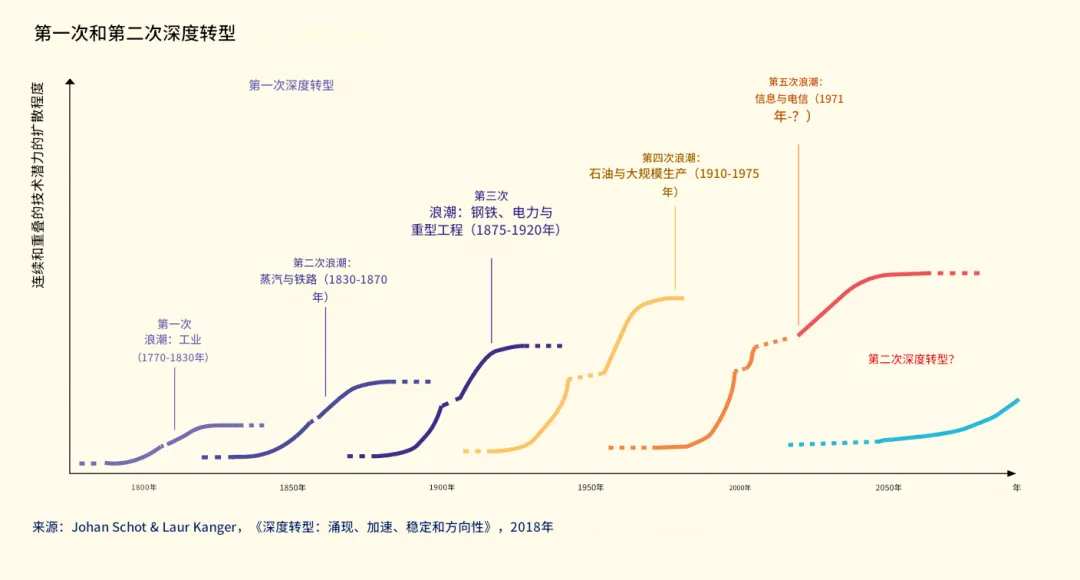

We have previously relied on Ian Morris’s theory of civilizational evolution and frequently referenced Carlotta Perez and her book Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital to understand how technological changes can trigger societal restructuring.

Our collaborative research with the University of Sussex also indicates that, despite producing a series of complex charts, the conclusion ultimately points to a straightforward assessment: we may be at the beginning of a new world, or even a 'new golden age.'

Perez herself remains cautious about such transformations. She notes that these transitions often require a financial bubble to create a window for change, but “we cannot expect a bubble to appear simply because we need one.” She also emphasizes that significant transformations generally require government intervention.

She may be correct. For instance, in China, under strong government leadership, certain transformations are quietly advancing.

In the current political context, after experiencing waves of neoliberalism and populism, the state intervention emphasized by Perez seems difficult to achieve. However, the seeds of transformation may already have been quietly sown.

For example, Californians’ enthusiasm for electric vehicles, while culturally influenced, is essentially an extension of legislative measures and incentives implemented decades ago. Europe’s push for a combustion engine ban following the 'Dieselgate' scandal also demonstrates the profound impact of institutional frameworks on future pathways.

Headline news is often dominated by figures like Trump and events such as Brexit, but perhaps the more significant variable lies in the institutional penetration of the 'green agenda' and climate policies. In the future, this could even reshape policy logic at the U.S. federal level.

05, The Fundamental Logic of Stock Returns

If structural changes in the economy and society define the possible boundaries of the market, we all recognize that macro trends alone are insufficient to sustain long-term exceptional stock price performance.

A company’s revenue and returns ultimately depend on its ability to maintain sustainable competitive advantages and whether its internal culture can continuously evolve and adapt.

The ability to identify moats is precisely the key to Buffett and Munger's long-term success.

However, just as neoclassical macroeconomics, which assumes a world that follows a bell-shaped distribution based on the premise of 'measurable risk,' has long struggled to address the complexities of reality, many traditional theoretical foundations of microeconomics have also become increasingly inadequate in explaining the successes and failures of today’s enterprises.

Especially one of its core assumptions—diminishing returns to scale—is facing unprecedented challenges in practice.

In many dominant firms, the importance of tangible assets continues to decline, and Tobin’s Q theory (which measures the ratio of a company’s market value to its replacement cost; if Q > 1, it indicates that the market valuation exceeds asset costs, incentivizing investment and expansion, whereas if Q < 1, the willingness to invest is low) is becoming increasingly difficult to uphold. Companies with enormous value on their balance sheets often possess few measurable physical assets; conversely, many enterprises with substantial tangible assets struggle to maintain a lasting competitive advantage.

Interestingly, Graham’s emphasis on the “unpredictability” of markets finds an echo in an unexpected direction.

One of the most thought-provoking works in recent years is Geoffrey West's *Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies*.

Despite being the former president of the Santa Fe Institute, his perspective in the book is counterintuitive: even in highly complex systems, there exist certain patterns that can be generalized and modeled, influencing the growth and decline of organizations.

West poses a highly challenging question: 'Can we establish a quantifiable and predictable science of companies to understand how businesses grow, mature, and ultimately come to an end?'

Based on his extensive research on companies and cities, cities exhibit strong characteristics of 'increasing returns to scale,' meaning they become more vibrant as they grow larger, with many key metrics showing 'superlinear scaling.' In contrast, companies do not follow this pattern, as most operational indicators scale sublinearly, resembling the growth trajectory of living organisms.

This implies that companies lack the structural capacity for infinite growth—they will eventually stagnate and may even perish.

This is precisely another mathematical articulation of what Graham referred to as 'the unpredictability of worldly affairs.'

West's conclusion is also straightforward: nearly all large, mature companies will eventually revert to the market's average growth rate.

However, this compelling macro trend has been challenged by some of the cases we mentioned earlier. Clearly, there have indeed been companies in the past few decades that achieved superlinear growth.

So, are these cases merely random 'noise,' or do they represent a deeper structural signal?

The answer to this question may determine the boundaries and orientation of 'growth investing' versus 'value investing' over the next few decades.

Our response is: there is no reason to rule out the possibility that more instances of 'superlinear growth' will emerge in the coming decades, which implies that the potential for extreme investment returns still exists.

As for the reasons, we must return to one of West's long-term collaborators, W. Brian Arthur.

Around the time when Microsoft’s business model was just beginning to take shape, Arthur started writing about the 'nature of returns.' This is no coincidence—after all, Microsoft was one of the classic cases in his research.

06. On Increasing Returns to Scale

Brian Arthur’s fundamental argument ran counter to the mainstream economics of the time: if certain firms experience 'increasing returns to scale' or even establish a positive feedback loop where 'the bigger they get, the faster they grow,' then their long-term value certainly warrants reevaluation.

In other words, such enterprises may exhibit genuine 'superlinear growth,' thereby challenging the West model and revising the fundamental assumptions of 'value investing.'

Looking further, the essence of these enterprises might no longer align with the traditional concept of a 'company'—they are more akin to 'cities,' acting as central nodes within ecosystems. Their advantages stem from network effects, platform status, and path dependency, rather than 'moats' or asset value.

This is not hindsight.

As early as 1939, economist John Hicks warned: 'Once the existence of increasing returns to scale is acknowledged, the entire edifice of economic theory risks collapse.'

For this reason, this concept not only overturns academic logic but also undermines the foundational strategies of market participants.

Brian Arthur’s summary of this phenomenon has become a classic:

“We can divide the economic world into two systems: one is a resource-intensive, large-scale production economy, where products are essentially crystallizations of resources with minimal knowledge involvement, following Marshallian diminishing returns principles;

the other is a knowledge-driven intelligent economy, where products are crystallizations of knowledge requiring very few resources, and the mechanism of growth follows increasing returns.”

From these two systems, expecting them to exhibit similar patterns in capital markets would be unrealistic.

Our numerous exchanges with Brian Arthur, along with his recent research and writings, indicate that he firmly believes the system of 'increasing returns' is becoming increasingly dominant.

Although this trend has already become somewhat evident in the market, from the perspective of practitioners, the resulting reconstruction of investment strategies is far from complete.

07. It’s not enough to only discuss theory; examples are also necessary.

One of Graham's writing talents was his ability to explain through company comparisons in a concise and incisive manner. For instance, Chapter Thirteen of 'The Intelligent Investor' compares 'Four Listed Companies' (ELTRA, Emery Air, Emhart, and Emerson Electric, with only the latter still existing as an independent entity); Chapter Seventeen presents 'Four Highly Instructive Cases'; and Chapter Eighteen consists entirely of 'Comparisons of Eight Groups of Companies.'

Jason Zweig later paid homage to this writing style by using modern examples.

I cannot replicate Graham's style or list as many companies, but I can attempt to present a comparative exercise in a concise manner. The purpose is not to advocate for growth investing but rather to illustrate the structure of corporate returns, their risks and rewards, which may reflect deep shifts in the economic structure over the past 35 years.

Coca-Cola

Choosing Coca-Cola as an example was a natural decision. For decades, it has been a core asset in Berkshire Hathaway's investment portfolio. Moreover, it serves as the central case in one of Charlie Munger’s classic expositions on investment foresight.

Munger began with this scenario: 'Imagine it’s January 1884, and you’re in Atlanta, Georgia... You and twenty others have been invited to propose a business plan that will turn a $2 million investment into a company worth $2 trillion by 2034.'

In 1996, Munger outlined his investment thesis for Coca-Cola, relying on just a few simple principles and straightforward mathematical reasoning. This calculation is essentially what we now refer to as the 'Total Addressable Market' (TAM).

True to form, he thought in reverse: To become a $2 trillion company by 2034, the global population (projected at 8 billion) would need to consume 64 ounces of water daily. If a quarter of that came from cleaner, tastier beverages, and your company captured half of that share, the market would reach 2.92 trillion servings of 8-ounce drinks.

If each unit generates a net profit of 4 cents, by 2034, this could result in profits of $117 billion, with room for further growth.

To achieve all of this, real-world incentives and psychological drivers must interact synergistically to create what Charlie Munger referred to as the 'lollapalooza effect'—an exponential amplification of motivations and rewards.

This approach did indeed help Coca-Cola build a great company and brought long-term substantial returns to Berkshire Hathaway. But the question is: Can it really achieve the $2 trillion target by 2034?

As early as the late 1990s, Coca-Cola’s market capitalization had already exceeded $175 billion. Considering reinvested dividends, Munger's goal, though ambitious, is not entirely out of reach.

However, over the past 20 years, its equity value has cumulatively grown by only about 12%. The $2 trillion mark remains far from reach.

Is this merely the cost of overvaluation?

After all, while Benjamin Graham deeply understood that long-term cash flow is the core of valuation, he still used the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio operationally to capture stock value and remained skeptical of any valuation above 20 times earnings.

By the end of 2018, Coca-Cola’s P/E ratio was approximately 23 times, with the market projecting its long-term growth at 6%–8%. Meanwhile, its price-to-book (P/B) ratio also reached double digits, which Graham would likely not have appreciated.

Regardless of whether it still qualifies as a classic value stock, a more pressing concern is that the 'lollapalooza effect' that once supported Coca-Cola now seems to be reversing. In 1884, it symbolized 'wealth, health, and modernity,' but by 2019, that symbolism had clearly faded.

In its 10-K report, Coca-Cola disclosed risks stating: 'Obesity and other health-related issues may lead to decreased demand'; 'Public discourse regarding potential health hazards of certain ingredients may also reduce demand.'

As a result, the company began to diversify into bottled water, juices, and even Costa Coffee, which, to some extent, reflects a wavering of confidence in its original vision.

From my personal perspective, what is more likely to emerge here is a 'negative lollapalooza effect.'

Facebook

In contrast, Facebook (now Meta), represents a typical high-growth company.

Facebook was labeled as a 'momentum stock' until recently, being one of the acronyms in 'FAANG,' coined by Jim Cramer. The mere inclusion of a company in one of Graham's abbreviations would be enough to send chills down his spine.

But if we temporarily set aside these labels, could we calmly compare Facebook and Coca-Cola in the manner Graham proposed in 'The Intelligent Investor,' to determine which aligns better with value investing principles and which is more worthy of long-term holding?

Facebook went public on May 18, 2012, at an initial price of $38 per share, with a static price-to-earnings ratio as high as 88 times. On the first trading day, the stock price once surged to $45, giving it a market capitalization exceeding $100 billion.

So, what was the situation by early February 2019? At that time, Facebook’s historical P/E ratio was approximately 22 times, and Nasdaq projected its average annual growth rate for the next five years to be between 15%–25%.

If we step outside the PE perspective and attempt a longer-term comparison, uncertainty naturally rises. However, Graham once proposed a mid-term valuation formula to assess a company’s fair value (although he later expressed reservations about its applicability).

For the sake of comparison, we can borrow this formula without harm: Valuation = Current (or normalized) earnings × (8.5 + 2 × expected growth rate).

By applying this formula, we can work backward to deduce the market's implied growth expectations for the two companies.

Take Coca-Cola as an example, with a corresponding growth rate of approximately 7.5%; surprisingly, Facebook’s implied growth rate is even slightly lower, falling short of 7%. This represents a significant gap from the market’s general forecast of 15%–25%, suggesting that Facebook might actually be 'undervalued' from this perspective.

Of course, such calculations may simply reinforce my skeptical tendencies. However, one point worth noting is that Coca-Cola had already indicated in its year-end guidance that profits in 2019 were expected to remain flat.

What would Graham think if he were alive today?

He might insist that Facebook is merely a short-term craze, with the market overhyping the illusion of high growth. But could it also be the opposite?

It may not be easy to determine which company relies more on the 'addiction mechanism.' However, viewed through the lens of Graham’s most valued principle of 'margin of safety,' Facebook may actually align more closely with his investment philosophy.

So, who is the true 'value stock'? And which is more attractive?

As George Orwell wrote in *Animal Farm*: 'In the end, you could hardly tell who was human and who was beast.'

08. The Marginal Upside That Cannot Be Ignored

But let us pause for a moment and attempt to reintroduce the previous discussion on systemic economic complexity into stock market analysis. It reminds us: we cannot predict earnings growth over the next decade, let alone further into the future. Yet acknowledging this profound uncertainty does not mean we are unable to draw any conclusions.

We can still construct different scenarios that incorporate the possibility of 'asymmetric high returns.' Furthermore, we can assign varying probabilities to these potential futures under a more open acceptance of skepticism.

This approach enables us to form a kind of 'informed judgment'—assessing whether, in certain scenarios, the upside potential significantly outweighs the downside risk.

I must admit, compared to the classic concept of the 'margin of safety,' I am more fascinated by the 'potential margin of upside.'

This asymmetric structure applies equally to Coca-Cola and Facebook, and it can reopen the debate between growth and value investing.

I am not entirely convinced that any company today can claim invulnerability to losses in the capital markets. In fact, for both companies, the risk of capital impairment cannot be entirely ruled out.

We also know that the products of both Coca-Cola and Facebook approach the boundary of 'addiction.' This characteristic serves as both a moat and a potential vulnerability. After all, from certain perspectives, consumers ceasing to use these products might actually be the healthier choice.

However, if we consider another angle: which company has greater potential upside?

Even without considering lower initial valuations and higher return rates, constructing an appealing scenario narrative or a related discounted cash flow (DCF) model for Facebook is much easier than for Coca-Cola.

In other words, both Instagram and WhatsApp demonstrate far stronger competitive advantages and growth potential than Dasani bottled water and Costa Coffee.

09. An example from the automotive industry

No industry features as frequently in investment debates as the automotive sector.

Why this is the case puzzles even me, as I hold no particular affinity for automobiles as a product. Over the past year, the debate has reached a boiling point – beyond traditional analyses of auto stocks, the rise of electric vehicles and specific discussions surrounding Tesla have made this industry especially emotional.

Amid such significant noise, the Graham-style 'company pairing comparison' approach may offer us a more dispassionate perspective for reflection.

In this industry, it is more appropriate to understand its full spectrum using a broader sample set – from value stocks to brand stocks, and to disruptive enterprises.

To that end, I have selected five companies spanning the entire spectrum of the automotive industry and stock market types:

General Motors

The first lifecycle of General Motors, despite ending in bankruptcy in 2009, still generated immense shareholder value. Research by Bessembinder shows that since 1926, it has been the eighth-largest 'wealth creator' in the history of U.S. equities.

Today's 'New GM' retains much of its original DNA while shedding the long-standing negative perception of 'managerial incompetence.'

Under the leadership of Mary Barra, the management team is highly respected. The company continues to invest heavily in electric vehicles and autonomous driving, proposing a brand vision of 'zero accidents, zero emissions, and zero congestion.'

In 2018, General Motors sold a total of 8.38 million vehicles, generating $4.4 billion in free cash flow and earnings per share of $5.72.

Based on Graham's valuation formula, the current market pricing of General Motors appears to reflect expectations of a slight decline in future returns (although analysts predict an average annual growth rate of approximately 8.5%). In other words, if you believe its performance volatility can be contained within a 'fluctuating but manageable' range, General Motors still aligns with the fundamental logic of value investing.

BMW

BMW is arguably Germany's most respected automobile brand, enjoying high recognition among consumers and strong acclaim from analysts. Its driving experience is highly praised, and its financial operations have consistently been robust.

Nevertheless, BMW today has fallen into the category of 'undervalued blue-chip stocks.'

Since its peak stock price in 2015 (around €120), the share price has steadily declined to the €70–€75 range. The company’s strong reputation has not translated into investment returns.

In 2017, BMW sold approximately 2.5 million vehicles, generating free cash flow of €4.46 billion (approximately $5.1 billion). In the first three quarters of 2018, free cash flow decreased by 25% year-over-year. The automotive industry places far greater emphasis on cash flow than profits, and BMW’s current valuation stands at just 6.5 times its estimated earnings for 2018.

The reasons for profit pressure are numerous: tightening diesel emission regulations, declining market share in California, weak demand in China, among others.

The concurrent decline in both the price-to-earnings ratio and free cash flow multiples suggests that, according to Graham's formula, the market expects BMW to enter a negative growth phase over the next five years. This assessment may reflect broader investor anxiety about structural changes within the industry.

Ferrari

If you believe that the automotive industry must rely on large-scale production capacity and is destined to struggle earning returns above the cost of capital, Ferrari serves as a counterexample.

In 2018, Ferrari sold only 9,251 vehicles but generated free cash flow of €405 million (US$463 million), representing a year-over-year increase of 23.5%.

This means: Ferrari's free cash flow per vehicle was €43,779, more than 10 times that of General Motors on a per-unit production basis, while its production volume was only one-thousandth of GM’s.

At a share price of €110, the Graham formula suggests that the market expects Ferrari to sustain an annualized earnings growth rate of 12.5% over the next 7–10 years. Although analysts currently project growth over a five-year horizon, Ferrari’s expected growth clearly outpaces the industry average.

Many observers argue that Ferrari should be regarded as a luxury brand rather than an automobile manufacturer. However, Chairman John Elkann, heir to the Agnelli family, disagrees. He emphasized: 'If Ferrari fails to remain at the forefront of automotive technology, neither its brand nor nostalgia will sustain its long-term success.'

If Ferrari’s current high returns prove sustainable, it is an exceptionally outstanding enterprise.

We must always be cautious about selling such companies lightly, as Philip Fisher once said: 'The right time to sell almost never comes.'

Tesla

Evaluating Tesla using Graham’s approach and relying solely on simple financial data appears more challenging.

After all, few companies evoke such intense market sentiment: founders, short-sellers, supporters, and critics are deeply intertwined, with discussions occurring at an extremely high frequency and emotional tension running strong.

So let us first examine the fundamental data.

Tesla recorded a net free cash outflow of $2.37 million for the full year of 2018. However, this figure was composed of two starkly contrasting halves: a net outflow of $1.7935 billion in the first half and a net inflow of $1.791 billion in the second half.

Such a dramatic reversal is clearly the result of Model 3 production ramp-up finally taking effect. However, whether this cash flow pattern is sustainable remains a matter of debate.

Of course, it is easy to view the performance in the second half as a 'leading signal' indicating future improvement trends. However, judged by Benjamin Graham’s extremely cautious standard toward optimistic forecasts, such judgment seems overly hasty.

What is certain is that to truly evaluate Tesla's value, we must introduce more forward-looking scenario assumptions. I will continue discussing this issue after the next example.

Nio

Despite the ongoing controversies surrounding Tesla, its investment logic is actually quite straightforward: it has virtually no real competitors in the electric vehicle markets of the US and Europe, and holds a dominant position in the pure-electric market. In terms of timing, it may be six to seven years ahead of other companies.

If you are confident in the appeal and economic viability of electric vehicles, the rationale for investing in Tesla becomes clear.

Nio, however, is entirely different.

There are nearly 500 Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers, and the entire market is in an extremely chaotic, fervent early stage, much like the state of the American auto industry in its early years before the rise of Henry Ford and General Motors.

Nio is not currently the market leader in China; the traditional leaders are$BYD (002594.SZ)$; Nio also lacks significant technological advantages, with most operations still outsourced to third parties.

Nio shows no clear prospect of nearing profitability, with negative free cash flow. There is little controversy on this point—were Benjamin Graham alive today, he would undoubtedly not invest in this company.

10. Overall Assessment of Auto Stocks

Now, we attempt to consolidate the preceding analysis. If you were a fair-minded value investor or growth investor, how should you evaluate these five automakers?

No matter how hard I try, it is difficult to construct a plausible 'mean reversion' theory that both explains past trends and serves as a valid basis for forecasting the future.

This applies not only to corporate fundamentals but also to their stock price performance.

Though this may not align with mathematicians’ strict definition of 'mean reversion,' I suspect the most common colloquial version in the auto industry is something like this: the profit per vehicle 'must eventually return to normal.'

This is why I previously emphasized the sales figures of each company.

This logic is often used to question Tesla—arguing that it sold only 245,000 vehicles in 2018, so 'how could it possibly be worth so much?' And how could it be compared to General Motors, Ford, or even Toyota?

Strangely enough, those confident and widely respected automotive industry analysts find it hard to imagine that BMW's high valuation and premium returns could change; in their eyes, those advantages are permanent and almost sacred.

As for Ferrari, people simply refuse to categorize it as a 'car company,' as if it naturally doesn't belong to this industry.

The issue lies in the fact that the fundamental characteristic of this industry has never been mean reversion but rather deep cyclical uncertainty, along with increasingly frequent disruptions and structural shifts today.

This reminds me of the 'parable of the turkey':

Every day, the turkey sees the farmer approach on schedule, receiving food without fail. Life seems unchanging, much like a perfect stock: stable dividends, extremely low volatility, and virtually no risk.

Until one day, the farmer slaughters it.

This is not far from the story of General Motors. From its founding in 1908 to its bankruptcy in 2009, General Motors weathered financial storms, shifts in wealth, and world wars, yet still enjoyed long-term prosperity. Even at the point of bankruptcy, it remained one of the companies that 'generated the most returns for shareholders' in U.S. stock market history.

If you had held it since 1926, your institution would likely have been satisfied; but if you bought in 2008, you might not have been so fortunate.

In other words, the logic of so-called 'mean reversion' simply does not apply here.

So how should we respond? Is there a way to navigate through the fog?

I believe there is. But only on one condition: we must rethink many conventional doctrines.

The intense volatility in the automotive industry tells us that attempting to predict the future with a single path is almost an illusion. What we are facing is an 'existential doubt': the belief that there is only one trajectory for the future, only one growth rate, and that all we need to do is plug it into a discount model—this is all overly simplistic.

This challenge has already become evident when comparing Coca-Cola with Facebook, and it becomes even more acute in the automotive industry.

What we need are multiple conceivable futures, ranging from the most optimistic scenarios to the worst-case 'turkey outcomes'.

With sufficient humility, we should assign probabilities to these scenarios and continuously update our assessments as reality evolves. On this basis, we should also expand the boundaries of 'extreme assumptions,' going far beyond the safe zones traditionally set by analysts.

This is not a binary framework of 'optimism vs. pessimism.' When envisioning upside scenarios, the focus should indeed be on 'creativity' rather than 'analytical ability'.

We return once again to Charlie Munger and Atlanta in 1884—a future world yet to be defined has never been born out of precise calculations.

Conversely, for downside scenarios, we should assume by default that bankruptcy is always a possibility for every company. Unless you have extremely compelling reasons, you should not dismiss it lightly.

This premise brings a sense of calm and clarity, forcing us to abandon the illusion of a 'margin of safety,' because you cannot demand absolute safety while expecting substantial investment returns.

However, it is precisely within this insecurity that the potential for true upside may emerge.

If we view automotive stocks through this lens, I believe it will lead to a more realistic assessment and is more likely to yield favorable investment returns, particularly when considered within the context of an overall portfolio rather than in isolation.

To that end, let us specifically examine where Tesla and Nio stand on the spectrum of potential returns.

What continually surprises me is that constructing a plausible scenario for Tesla that significantly exceeds its current market valuation is not difficult. In fact, compared to most of the investment targets we study, it requires less imagination.

This may be because Tesla only needs to capture market share within existing markets to potentially deliver explosive growth; whereas many internet platform companies must first create an entirely new ecosystem.

Of course, we cannot rule out the possibility of Tesla experiencing a sharp decline or even bankruptcy. Even as recently as six months ago, such an assessment would have been reasonable. Today, the likelihood of a 75% drop in share price still exists.

But the question arises: Isn’t this precisely the kind of opportunity structure we should embrace? A return distribution that is 'highly skewed, asymmetric, and awe-inspiring.'

This is the essence of buying growth at an unreasonable price.

We can begin constructing this bullish scenario with the Model 3:

Assuming annual sales reach 1.5 million units—a figure that is already realistically attainable within the current luxury car market, especially following a demand shock akin to the iPhone's disruption of Nokia.

Considering that the average selling price of the Model 3 is significantly higher than the entry-level price of $35,000, achieving annual revenues of $75 billion is not an exaggeration.

The current operating profit margin stands at 5.8%, but the long-term target is close to double digits, with a gross margin target even reaching 30%. Given Tesla's vertical integration advantages in batteries, supply chain, technology, and data control, its profitability may remain at a high level.

Now, we are not forecasting the central scenario but rather outlining the possible upper limit. Assuming an operating profit margin of 20% and a net profit margin of 16%, annual net profits would reach $12 billion; if capital expenditures are primarily maintenance-related, free cash flow would be roughly equivalent.

At a free cash flow yield of 3% (referencing Ferrari's 2.5%), the reasonable market valuation five years from now would be $400 billion.

What is the probability of such a scenario occurring?

It is not the mainstream expectation, but it is far from being unrealistic. Within this time frame, Tesla’s competitive moat appears solid, supported by customer loyalty and satisfaction. Even under conservative estimates, we can assign it a probability weight of 20%.

More importantly, the Model 3 is not the sole growth driver: the Model Y targets a broader market with higher pricing potential; the Tesla Semi (truck) is about to launch, opening the commercial vehicle segment; Tesla Energy, with stronger execution capabilities, is gradually unlocking its potential; and the commercialization of autonomous driving and software upgrades continues to advance.

The path with the highest uncertainty but potentially the greatest return is full self-driving.

Although Tesla’s chosen path is not mainstream, its probability of success has risen from 'almost zero' to 'still unlikely.' However, if achieved, the resulting value would be almost incalculable.

As Elon Musk told us six years ago: 'The possibility of Tesla becoming the largest company in the world, though small, is increasing.'

Today, that statement no longer sounds absurd.

Of course, all of this still does not constitute certainty.

Compared with Tesla, Nio's future is harder to predict. We must acknowledge that, among all possible scenarios, there is a significant probability that the company’s stock price will eventually approach zero or near zero.

To avoid getting bogged down in details, let us directly present the boundaries of our valuation range:

30% probability: value drops to zero; 5% probability: achieves a 65x return.

This is a typical 'extreme scenario,' as Taleb would say. In such a world, the term 'margin of safety' seems utterly absurd, and 'mean' is equally irrelevant.

The only thing that truly matters is the enticing 'asymmetric return' under path dependency.

Of course, before navigating these abysses, Nio should occupy only a tiny portion of your diversified investment portfolio. However, we believe that the leadership team’s vision and strategic boldness do indeed create some possibility.

The core point I want to emphasize most is this: for both Tesla and Nio, despite an uncertain and challenging future with diverse pathways, the 'probability-weighted upside potential' genuinely exists and is highly attractive.

By contrast, the situations of BMW and General Motors are entirely different. Even if BMW successfully survives the transition to electric vehicles, the best-case scenario would merely be a return to its previous valuation, rather than delivering exponential excess returns within a portfolio.

As for General Motors, any sustained rise in its stock price would almost entirely depend on the success of its 'electrification and automation' transformation strategy. And we all know that fundamentally reshaping a century-old company is far more difficult than building a new one from scratch.

11. The Principles and Mindset of Shareholder Activism

In fact, Benjamin Graham once expressed his disappointment with corporate governance in his writings:

"Since 1934, we have been advocating in our writings that shareholders should adopt a more intelligent and proactive attitude towards management... but the idea that public shareholders can truly help themselves by supporting initiatives to improve management and policies has proven to be too quixotic to merit further discussion in this book."

As Jason Zweig pointed out, this statement was not a rhetorical aside but rather Graham's candid conclusion after his disillusionment with reality. In subsequent editions, three-quarters of this section was removed; the only hope he retained was for the wave of 'hostile takeovers.'

So what about today? Are shareholders still powerless in practice? Is everything still as Graham described it back then?

I do not think so. In fact, the ecosystem of corporate governance has undergone structural changes today, with at least three aspects being particularly prominent:

First, the rise of institutional investment. This change has profoundly shaped the governance culture. Quarterly expectations for financial reports, anxiety over continuous growth, and an obsession with stable dividends have, through round after round of surveys, votes, meetings, and window guidance, created a persistent and systematic pressure.

This is no longer a lack of oversight but has instead evolved into institutionalized short-termism.

Second, the rise of activist hedge funds. From J.C. Penney, Sears, to Sony, Nestlé, and Barclays, almost every major company has become a target. In the first half of 2018 alone, there were 145 activist campaigns globally, involving 136 companies, with Elliott alone initiating up to 17 campaigns.

Many of these have gone far beyond the purifying function of traditional short selling, evolving into amplifiers of short-term pressures.

Third is the expansion of governance teams. Whether it is asset management institutions or governance advisory firms, equipping a corporate governance team has almost become standard practice. Their original intention was to promote long-term governance quality, but if they fall into flawed logic, they instead become a new form of bureaucratic force. They believe that a unified policy (preferably a manual, at worst a set of rules) can be universally applied to any enterprise.

This compliance-driven governance style often emphasizes details over principles in execution, running counter to the concept of truly responsible governance.

Imposing a one-size-fits-all governance template on companies with varying global scopes, stages of development, and corporate cultures is undoubtedly absurd.

I am not complaining; rather, I am attempting to respond.

I wish to advocate for an alternative approach: in a world full of complexity, uncertainty, and path dependence, a few clear principles are far more effective than an elaborate set of regulations. This, in essence, is also a manifestation of competitive advantage.

As John Kay stated 25 years ago, 'The essence of corporate strategy lies in aligning internal capabilities with external relationships.'

And he recently added, 'Carrots and sticks certainly have their uses. But when you are dealing with talented individuals operating under uncertainty, these tools prove insufficient.'

For us as investors who support high-growth enterprises, this judgment is particularly crucial. The companies we select resemble agile and exceptional racehorses rather than donkeys that can be easily driven.

In an era rich with opportunities but lacking clear paths, top-down directive governance often represents the worst possible solution.

So what can we do?

In my view, the most important thing is to establish a primary principle, supported by three modes of thinking.

This principle is: we should encourage companies to focus all their efforts on a qualitative ultimate goal—building long-term competitive advantages, rather than chasing short-term financial metrics. As long as companies are guided by this principle and proceed in a rational and restrained manner, we will be firm supporters.

This also means that companies must build and strengthen their uniqueness rather than mechanically conforming to the best practices defined by the market. True competitive advantage cannot arise from the execution of a generic template but can only emerge from a distinct capability structure and cultural shaping.

The three modes of thinking that accompany this principle are also specific manifestations of our investment philosophy:

First, as long-term investors, we also hope that corporate culture has longevity. Often, whether such a culture can be established depends on whether the company has a leader with both vision and a secure position.

Second, even the best companies will inevitably experience downturns. For us, when the '13 bad weeks' arrive, we are more inclined to offer understanding rather than punishment. Because we know it will come sooner or later.

Third, if we understand the potential opportunities a company faces and believe that the possible returns could cover the risks, then even if the effort ultimately fails, we are still willing to applaud such an endeavor.

In short, we aim to reclaim the definition of 'shareholder activism,' not only to speak for growth-oriented companies but also to advocate against destructive hedge funds and rigid governance templates.

12. The divide between growth and value is not so significant.

As this journey nears its end, I remain internally conflicted. However, I increasingly tend to believe that Benjamin Graham’s wonderful and stable investment world is difficult to return to.

This is not because his theory was wrong, but precisely because he and his followers were too successful.

As Charlie Munger quipped at the age of 95:

"Now there is a group of Graham-style fund managers, like a group of cod fishermen, still casting their nets in the same waters long after the cod have been fished out. They aren’t catching much anymore, but they keep on fishing."

But the issue isn’t just that the ‘value investing waters’ have been overfished; more fundamentally, reality has undergone profound structural changes.

Over the past few decades, a group of great growth companies have defied the logical skepticism once posed by Graham and overturned the doctrine of 'mean reversion.' These companies have not only survived for the long term but also continued to grow sustainably even at an extremely large scale.

This is not merely a matter of opinion but a statistical fact supported by data.

Their existence has reshaped the entire market’s return distribution and even undermined the analytical value of the concept of 'mean' itself.

Today, the gap between the mean and the median is so large that it forces us to rethink the structure of the entire distribution curve.

Our first real opportunity to reassess all of this came more than 30 years ago during Microsoft's rise. Ironically, the investment industry as a whole has been extremely slow to adjust its understanding.

We may be able to respond to earnings reports within seconds, yet it has taken us decades to update our worldview.

However, the existence of 'growth black swans' can actually be incorporated into a more structural methodological framework to rethink our understanding of companies and the economic world.

If we acknowledge that we are in an economic system driven by technology, knowledge, and network effects, which is complex in structure and highly path-dependent, then we should also expect that a few fortunate outlier companies will continue to defy conventional skepticism and deliver highly asymmetric returns.

In such a world, Brian Arthur's theory of 'increasing returns to scale' may well be the most critical intellectual tool for understanding modern markets. Moreover, the phenomena it explains are growing in significance across the entire investment landscape year by year.

In other words, it is time for those still entrenched in 'Modern Portfolio Theory' and 'equilibrium economics' models to stop viewing themselves as the spokespersons of rationality and science. They may need more humility and should consider reading some different books.

The Graham-style world still works in certain areas, but these regions are shrinking year by year.

How should we view the future?

We have every reason to believe that the proportion of the economy driven by knowledge, technology, and network effects will continue to rise. One of the key drivers behind this trend is the increasing importance of data acquisition capabilities.

As technology executive and artificial intelligence expert Kai-Fu Lee pointed out, 'Even the best data scientist cannot compete with a mediocre opponent who has more data.'

This is the ultimate manifestation of the logic of 'increasing returns to scale.' In such markets, first movers not only lead but accelerate further ahead.

However, in the stock market, we must remain vigilant on several fronts.

First, although the majority of market participants and asset allocators continue to doubt the legitimacy of growth investing, for which we have also paid a price, the reality is that growth investing has dominated the market for years.

What we should truly be concerned about is not mean reversion but market foresight: once the logic of growth is widely embraced by the entire investment industry, that will mark the true “Ides of March” for the stock market. However, for now, that day seems far off.

Second, the public equity market is becoming increasingly unfriendly to companies with high capital expenditures and high uncertainty. The next generation of entrepreneurs may simply be unwilling to bear the intense pressures that come with going public. After all, venture capital is abundant today and offers longer tolerance periods—so why would they subject themselves to such hardship?

This is the crux of the issue: many genuine platform-level growth companies already exhibit an “increasing returns structure” before they become profitable or even go public. Traditional value strategies, and even index funds, are unable to capture this early-stage value creation.

The alternative path offered by venture capital is equally significant when understanding equity return structures.

An increasing body of research shows that the return structure of publicly traded stocks more closely resembles venture capital than the kind of 'stable annual compounding' envisioned by Graham.

This means that the value generated by one success far outweighs the losses from several failures. This indeed poses a challenge to the traditional approach of value investing.

Graham’s classic adage still rings clear: 'Rule No. 1: Do not lose money. Rule No. 2: Never forget Rule No. 1.' But from a true portfolio perspective, this may not be the wisest strategy.

Finally, we must acknowledge an unsettling similarity that aligns perfectly with the 'self-reinforcing, path-dependent, and ultimately irreversible growth trends' discussed earlier—this is the logical structure of climate change.

Climate change also exhibits extreme path dependency and irreversibility, with potential impacts on the global economy so vast as to be almost unimaginable.

Against this backdrop, the debate between value and growth may ultimately seem as trivial as medieval theologians arguing over 'how many angels can dance on the head of a pin.'

However, beneath the clamor of the 'growth vs. value' debate, we can still draw nourishment from many of the excellent traditions of value investing.

It expresses ideas with greater depth and provides a better definition of the moral objectives and practical significance of investing.

It emphasizes patience, a highly valuable quality in investing.

As long as we can avoid an obsession with questionable metrics such as 'low P/E ratios' or 'low P/B ratios' and refrain from using 'mean reversion' to dismiss decades of consistently outstanding company performance, then we are not truly at odds.

If I could tell a growth story about Coca-Cola in 1884 like Charlie Munger, I would feel deeply gratified. Isn't that a more sophisticated logic of long-term growth?

It relies not on analysis but on imagination; it explains why long-term returns do not revert to the mean and why one should not be constrained by asset multiples; it considers what founders and management should and should not do; it acknowledges uncertainty while still embracing the possibility of a vast addressable market.

Perhaps, the differences between us have never been as great as they appear.

![]() Futubull[Opportunity Page]The tracking feature for celebrity portfolio opportunities has been officially launched! Explore a variety of portfolios held by renowned investors, follow their strategies with a single click, precisely target high-quality assets, and invest with greater confidence!

Futubull[Opportunity Page]The tracking feature for celebrity portfolio opportunities has been officially launched! Explore a variety of portfolios held by renowned investors, follow their strategies with a single click, precisely target high-quality assets, and invest with greater confidence!

Editor /rice