This article is from: Thought Steel Seal

01 It’s not the wind moving, it’s the heart moving

Fund A has an annualized return rate of 15% over the long term, but during market corrections, it often experiences drawdowns exceeding 20%. Fund B has a long-term annualized return rate of 10%, but during each market correction, its drawdown does not exceed 5%. Which fund do you think is better?

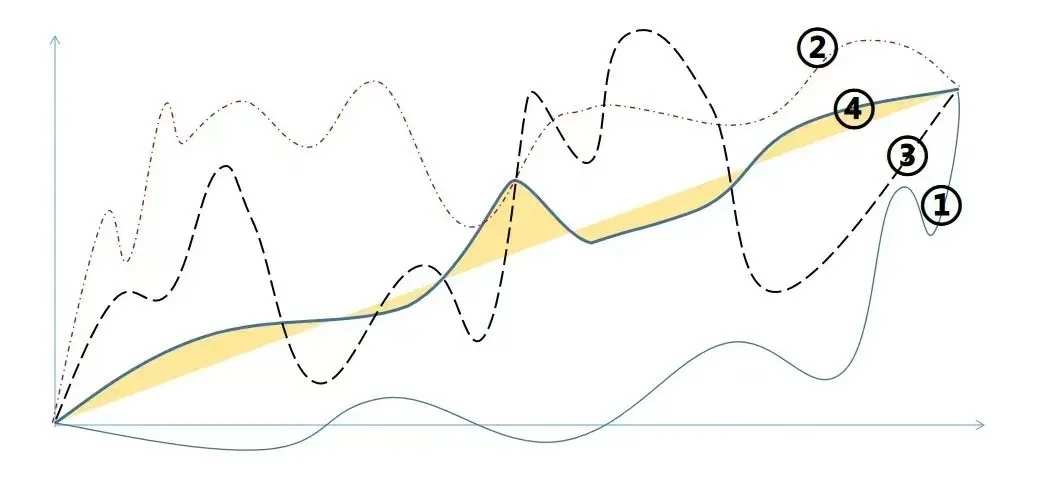

This question is similar to the diagram below, which I have referenced in several previous articles. Several stocks have identical returns, but ordinary investors tend to make more money on those with smaller fluctuations.

Fluctuation is an issue that is easily overlooked. Most investors focus only on the direction, but many people who correctly predict the direction still lose money due to volatility.

Fluctuation is an issue that is easily overlooked. Most investors focus only on the direction, but many people who correctly predict the direction still lose money due to volatility.

Many people view 'withstanding volatility' as a mindset issue separate from investment analysis capabilities—it’s not the wind moving, nor the banner swaying, but your heart that is stirring. However, in academia, volatility is not an intangible mindset issue but a tangible risk.

Of course, there are also many practical-minded investment masters who oppose the view that volatility equals risk. Their perspectives can be divided into two camps: one believes that volatility is neutral, and the other believes that volatility itself is a source of returns.

Being able to understand the value of a company or asset makes you merely a good researcher; only by understanding the fluctuation of assets can you become an excellent investor. This article will break down the concept of 'volatility' into several layers of meaning.

02 Academic Perspective: Volatility = Risk

The golden metric for evaluating fund performance, the 'Sharpe Ratio,' suggests that one should not only look at a fund’s rate of return but also assess the level of risk undertaken to achieve that return.

But how should risk be evaluated?

From the perspective of traditional financial investment theory, such as Markowitz's Modern Portfolio Theory, risk is defined as the uncertainty of future returns, which manifests as price volatility.

Many people do not agree with the notion that 'volatility equals risk.' Volatility is merely a temporary change in stock prices, and investors do not actually incur losses. However, this is just an illusion of 'mean reversion' created by the term itself. 'Volatility' is viewed retrospectively, but when the stock price plunges, you cannot predict the future—whether it will continue to decline or rebound.

At the end of 2013, assuming an investor confidently told you that Moutai was only facing temporary difficulties, with its stock price experiencing a mere fluctuation and future performance expected to recover, resulting in a rising share price. This investor undoubtedly demonstrated remarkable foresight. However, if he happened to encounter an urgent need for funds due to family issues at this time, he would have no choice but to sell at 80 yuan (adjusted price), bearing the losses caused by this volatility.

Similarly, those holding Maotai shares now may see their prediction come true as the stock replicates its glory from 2015-2021, but if they need cash urgently, they can only sell at the current price.

Although investment targets the future, trading happens in the present. Volatility appears as a process when viewed in the future, but in the present, it represents an outcome.

Therefore, when quantifying risk, the Sharpe Ratio uses the standard deviation of historical return volatility. Standard deviation is a statistical method. If several stocks have the same return, but Stock A has higher volatility than Stock B, then Stock A carries more risk.

A fund with an annualized return of 15%, a risk-free rate of 3%, and a standard deviation of volatility at 12% has a Sharpe ratio of 1, indicating that for every 1% of risk taken, there is 1% of excess return.

The volatility of Alibaba over the past 52 weeks is twice that of NetEase. If you want to buy Alibaba, you need to ensure that your calculated expected return is double that of NetEase; otherwise, the risk-reward ratio would not be worthwhile.

Whether or not you accept it, volatility equals risk. The greater the volatility, the higher the risk, necessitating a higher expected return as compensation. This is the actual pricing principle of modern asset classes. Here are two examples:

Example one: The dividend yield of high-dividend stocks is usually higher than the yield of bonds. Even for companies with very stable operations like Yangtze Power, this is true because the volatility of stock prices is much higher than that of bond prices. To achieve the same 'risk-adjusted return,' the dividend yield of Yangtze Power must be higher than the bond yield. The excess part is called the risk premium, and its quantified form is volatility.

Example two: As mentioned at the beginning, Fund A has a long-term annualized return of 15%, but during market corrections, drawdowns often exceed 20%. Fund B has a long-term annualized return of 10%, but during market corrections, drawdowns do not exceed 5%. If you were to calculate the average return of all investors, you would find that the average return of Fund B's investors will far exceed that of Fund A.

Losses due to volatility are real. The average return of all historical investors in A-share funds is likely negative because funds with high returns and high volatility tend to experience 'net subscriptions at peaks and net redemptions at troughs.' Conversely, funds with low volatility may see net subscriptions at troughs.

The difference between the actual return of investors and the fund's own annualized return also reflects the concept that 'volatility equals risk.' Therefore, inexperienced retail investors focus only on returns, while professional FOFs prioritize the Sharpe ratio.

However, Buffett explicitly rejected the traditional investment perspective that 'volatility equals risk.'

03 Practical Perspective: Volatility ≠ Risk

At the 2008 annual shareholders' meeting, Buffett reiterated his view on the notion that volatility equals risk when responding to shareholder questions: 'In assessing risk, we consider volatility meaningless. The risk that matters most to us is the permanent loss of capital.'

He explained:

You can find all kinds of good companies that have high volatility and strong profitability, but this does not make them poor businesses. At the same time, you may also come across businesses with very low volatility that are actually terrible investments.

Value investing masters like Howard Marks have criticized the conventional notion of equating volatility with risk, arguing that it oversimplifies the real world for the sake of academic convenience.

Buffett did not say that 'volatility is not risk'; rather, his point was that volatility is a neutral concept unrelated to risk.

This is understandable since Buffett focuses solely on a company's intrinsic value. For long-term investors like Buffett, short-term fluctuations are merely 'noise,' neutral in nature and posing no substantive threat unless one is forced to sell at a low point.

In fact, Buffett's understanding of volatility has evolved over time. During his earlier 'cigar butt' phase—where 'cigar butt' refers to investing in companies that may not be great but whose stock prices are so low they offer value even for one last puff—the essence was leveraging downward volatility as an opportunity to make profits.

Buffett has almost always emphasized in his annual letters to shareholders that his strategy is to 'buy low.'

In the 1963 letter to shareholders, it was stated: Our business is to buy undervalued securities and achieve an average rate of return higher than that of the Dow Jones Index.

In the 1965 letter to shareholders, it was said: We seek securities that are sold below their intrinsic value. The larger the margin of safety, the better we can withstand market volatility.

In fact, the early Buffett did not consider volatility as neutral but rather as a significant source of returns. This concept also serves as a core theoretical foundation for various investment strategies.

04 Trading Perspective: Volatility = Returns

The perspective that 'Volatility = Returns' must still be understood from the viewpoint of 'Volatility = Risk'.

Behind this perspective lies the reality that many investors dislike uncertainty and are averse to volatility, especially large institutional funds. For instance, do you think sovereign wealth funds or national teams like volatility? Do social security funds like volatility? Do insurance funds like volatility?

It's not just risk-averse institutional investors; high-net-worth individuals generally dislike income volatility more than ordinary people. The psychology behind this is simple: for the wealthy, earning more money won't significantly improve their standard of living, while ordinary people often feel they have nothing much to lose (though this is not true), believing that having more money can greatly change their lives (which is true).

Due to the Pareto Principle (80/20 rule), where 80% of wealth is held by 20% of high-net-worth individuals, asset pricing also reflects risk aversion. High-volatility risky assets typically trade at a 'discount.' For example, the dividend yield of stocks being higher than bond yields essentially means that stocks are trading at a discount (from the perspective of intrinsic yield similar to bonds).

However, risk itself is an objective reality. If subjective risk pricing exceeds objective facts due to risk aversion, it implies that part of the potential return of the risky asset transfers from risk-averse investors to risk-seeking investors.

One person’s risk to avoid becomes another person’s opportunity for gain, akin to Littlefinger’s famous line in 'Game of Thrones': 'Chaos is a ladder.'

Therefore, 'volatility = return' is actually the flip side of 'volatility = risk'.

This form of profit transfer is known as volatility trading.

Risk is a 'commodity' that can be both bought and sold, with insurance being the most typical example. Insurance companies earn premiums, while those purchasing insurance transfer a portion of their total asset returns to the insurance company in the form of premiums.

Since volatility equals risk, 'volatility' can also become a tradable 'commodity,' with options being the most typical example.

The pricing of at-the-money options (stock price = strike price) is related to volatility. For two different stocks with the same expiration period and strike price, the higher-priced at-the-money option is typically due to a higher historical volatility. The buyer of the option (equivalent to the insured party) faces higher odds, resulting in a more expensive option price. The seller of the option (equivalent to the insurance company) must charge a higher option price to cover the risk.

Among the seven giants, Tesla has the highest pricing for at-the-money options (implied volatility), followed by NVIDIA, then Google and Amazon, with Apple and Meta further behind, and Microsoft having the lowest, reflecting their varying historical volatilities.

Volatility is not about the philosophical debate of 'whether it’s the wind moving, the banner moving, or the mind moving,' but rather represents tangible risks and returns.

Based on differing attitudes towards volatility, investment strategies can be divided into two types: directional trading strategies and volatility trading strategies.

Among traditional equity investors, whether they are value investors or trend traders, although opinions on volatility vary, conservative investors dislike volatility while value investors consider it an irrelevant factor. However, direction remains paramount; if the directional bet is wrong, losses are inevitable, making volatility an objective risk.

However, there are also many strategies where returns depend not only on direction but also on volatility.

The most familiar strategy to many is dollar-cost averaging, which works best when a 'smile curve' occurs — a drop followed by a rise — with part of the returns derived from volatility.

More focused on volatility than dollar-cost averaging is the 'grid trading strategy,' which specializes in mean reversion and purely profits from volatility. Direction, in contrast, can be harmful; upward breakouts result in lost positions, while downward breakouts lead to permanent losses. Thus, the most suitable assets for grid trading are convertible bonds with a 'ceiling above and floor below.'

In contrast to grid trading is 'trend trading,' which focuses on breakouts and is a strategy where both direction and volatility are equally important. The essence of a 'breakout' is volatility constrained within a price range that suddenly expands after the price moves out of the range. In commodity futures trading, where positions can be either long or short, one must first correctly predict the directional bias (long or short) and then assess the speed of the breakout. Getting both right leads to significant gains (KTV), but getting one wrong results in losses; getting both wrong could lead to catastrophic outcomes (ICU).

Trend trading is thrilling, but in the eyes of pure options traders, betting on direction is meaningless gambling. They seek returns solely from volatility, using option combinations to hedge out directional exposure and even eliminate elasticity (Delta), leaving only the pure impact of volatility.

Even among volatility trading strategies, risks and returns differ. Grid trading prefers moderate and stable volatility, neither too high nor too low. In contrast, options-based volatility trading strategies have specific approaches for rising or falling volatility but fear unchanging volatility or incorrectly predicting its direction most of all.

05 Volatility is the essence of the financial world.

To begin with, let us revisit the main argument of this article:

Volatility is not risk itself; the true risk is 'permanent loss.' However, volatility is the manifestation of risk: it triggers investors' fear and behavioral biases, turning risk into reality and providing counterparties with profit opportunities.

From this, three perspectives on volatility emerge:

Risk-averse individuals believe that volatility equals risk and should be avoided.

Risk-seeking individuals believe that volatility equals returns and should be embraced.

Value investors consider volatility to be neutral, believing that investment risk only stems from permanent losses caused by business operation risks.

All three attitudes have profitable strategies, with their core lying in understanding what can be judged and what cannot:

Institutional investors, through multi-asset portfolios and robust research capabilities, believe that returns are controllable, but investor psychology is not. Thus, they choose to manage volatility.

Investors seeking high returns believe they can manage their mindset in the face of continuous losses and significant drawdowns, willingly betting on both direction and volatility to achieve higher yields, thereby embracing volatility more actively.

Value investors believe that market volatility is uncontrollable, but the ability to assess corporate value can be improved. They adopt a neutral and detached attitude toward short-term stock price fluctuations.

Regarding volatility itself, it is essential to distinguish between what can be predicted and what cannot:

Some investors believe that predicting the magnitude of volatility is more challenging, but the direction of volatility is relatively easier to predict, such as with the pendulum theory, leading to various timing strategies based on mean reversion and trend trading;

Other investors think that while the direction of volatility is difficult to predict, changes in volatility follow certain patterns, so they prefer to design directionally neutral volatility trading strategies.

When it comes to how to utilize volatility, it is also necessary to differentiate between what can be judged and what cannot:

Some investors hold the view that humans have inherent response patterns when facing volatility, many of which are behavioral biases, resulting in numerous strategies targeting these behavioral biases, commonly referred to as 'harvesting韭菜'.

Other investors believe that due to human behavioral biases in the face of volatility, on one hand, many trading opportunities are created, while on the other hand, they themselves also exhibit behavioral biases. Consequently, they have developed many quantitative strategies that are automatically executed or even autonomously learned by machines.

Therefore, volatility is not an anomaly but rather an inherent characteristic of the financial world. It reminds us that the world is constantly changing and compels us to distinguish between what we can control and what we cannot, as well as what we can judge and what remains beyond our judgment.

![]() Looking to pick stocks or analyze them? Want to know the opportunities and risks in your portfolio? For all investment-related questions,just ask Futubull AI!

Looking to pick stocks or analyze them? Want to know the opportunities and risks in your portfolio? For all investment-related questions,just ask Futubull AI!

Editor/KOKO